CAA 2024 Update Explained: What the New Order Really Means

You might remember the heated debates, protests, and endless discussions around the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) back in 2019. Last year, the government finally implemented it, and now it’s back in the headlines again. Why? Because the cut-off date has been extended to 2024. Many people are confused: Does this mean more people can now apply for Indian citizenship? Or is it just a temporary relief? Let’s break it down in simple words so you know exactly what has changed.

What Was the Original CAA?

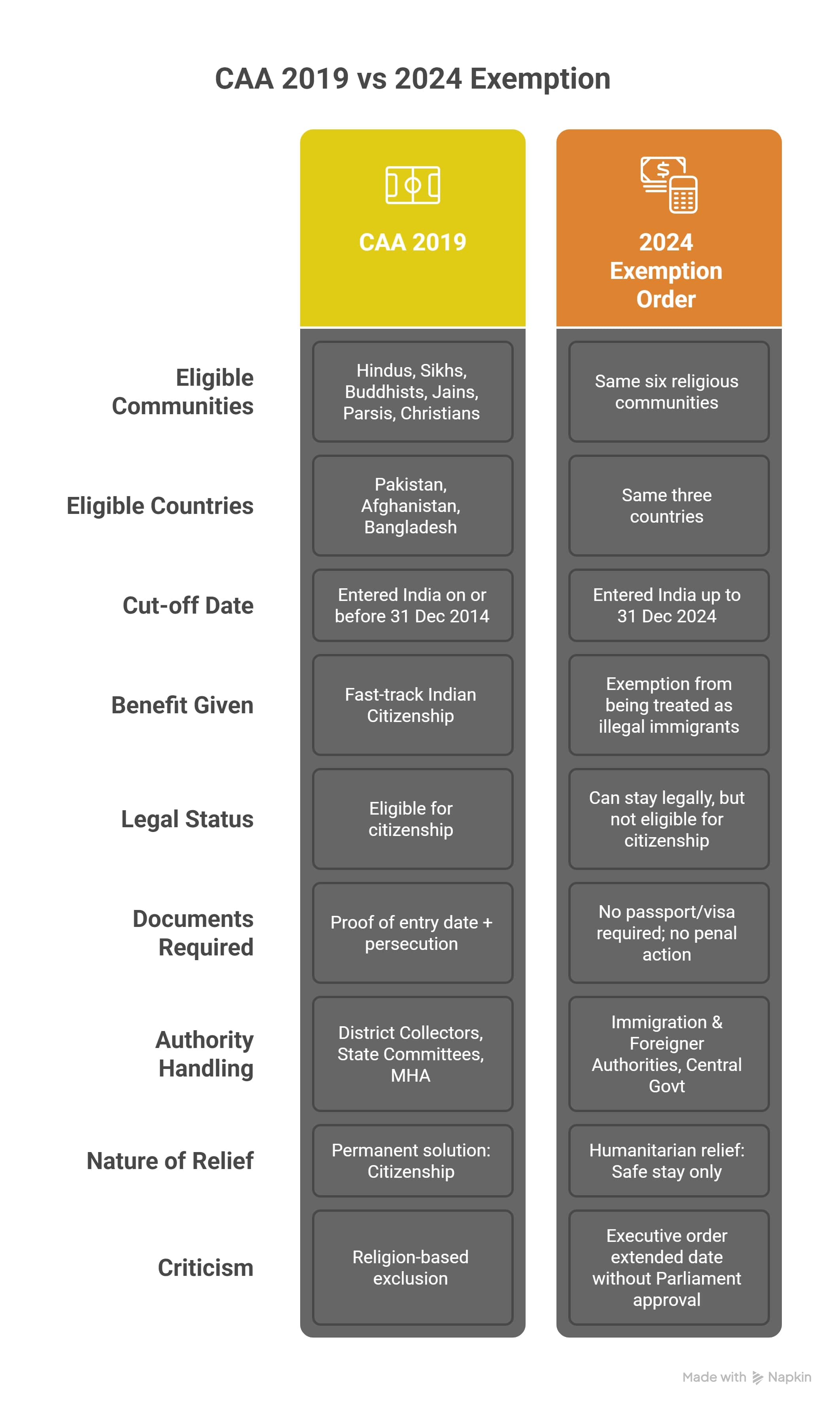

The Citizenship Amendment Act, passed in 2019, was meant to provide fast-track Indian citizenship to persecuted minorities — Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians — from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh.

- The cut-off date was 31st December 2014.

- If someone entered India on or before this date, they could apply for citizenship under CAA.

- The idea: protect minorities facing religious persecution in those countries.

But the law sparked controversy because it excluded Muslim minorities like Ahmadiyyas, Shias, and Hazaras, who also face severe persecution.

What Has Changed Now?

On 31st August 2025, the government issued a new Immigration and Foreigners Exemption Order.

- Now, minorities (the same six groups) from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh who entered up to 31st December 2024 are exempted from passport and visa requirements.

- They will not be treated as illegal immigrants.

- They will be protected from arrest, detention, or deportation.

Key point: This does not mean they get citizenship. Citizenship still applies only to those who entered before 31st December 2014.

Why This Matters

Thousands of people entered India between 2015–2024 due to ongoing persecution. Without this exemption, they would be considered illegal immigrants.

- With the new order, they can legally reside in India.

- They can also leave and return without the fear of detention.

- It provides a humanitarian safety net without extending full citizenship.

Why the Confusion?

The headlines made it sound like the cut-off date for citizenship was extended. But the reality is different:

- Citizenship: Still limited to those who entered before 31st Dec 2014.

- Exemption from being illegal: Extended to those who entered up to 31st Dec 2024.

Think of it as two different tracks: one for citizenship, and one for legal protection.

The Politics Around It

Supporters of the move call it compassionate. They argue persecution did not magically stop in 2014, so giving relief to those who came later makes sense.

Critics say it’s unconstitutional — extending exemptions without amending the law in Parliament is questionable. Opposition leaders also warn of demographic shifts in northeastern states, where migration has long been a sensitive issue.

This will likely end up in the Supreme Court for judicial review.

The Background of Persecution

- Pakistan: Minority population fell from 15% at Partition to less than 2% today. Blasphemy laws, forced conversions, and attacks are common.

- Bangladesh: Hindus dropped from ~30% of the population to around 8%. Attacks often spike during political unrest.

- Afghanistan: From ~200,000 Hindus and Sikhs in the 1970s to fewer than 200 today. Taliban rule drove most away.

This is why India argues that humanitarian relief is necessary.

Main Criticism of CAA

The core criticism remains: Why exclude Muslim minorities?

- Groups like Rohingyas (from Myanmar), Ahmadiyyas and Shias (from Pakistan), and Hazaras (from Afghanistan) also face brutal persecution.

- The government’s stance: CAA is not a global refugee law, but a targeted humanitarian measure for specific communities.

What This Means for India

- For affected minorities: A lifeline to live without fear of deportation.

- For the government: A politically sensitive move before elections, balancing compassion with legal limits.

- For the courts: A potential case on whether the extension without amendment is valid.

Conclusion

The CAA 2024 update doesn’t expand citizenship — it expands protection. For persecuted minorities, it’s a shield from fear. For India, it’s another chapter in a deeply debated law that blends humanitarian relief with political strategy. As discussions continue, one thing is clear: the question of who belongs, and how India balances compassion with law, will remain at the centre of national debate.

What do you think — does this new order strike the right balance, or should the government go further? Share your thoughts in the comments.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!